Rights Groups Question Malaysian Govt’s Reform Efforts

2019.05.08

Kuala Lumpur

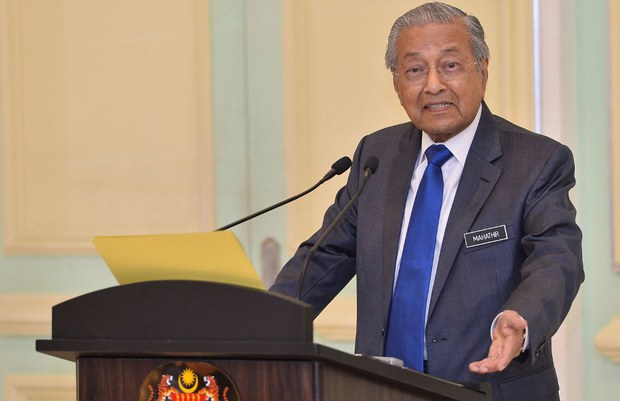

Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad speaks to reporters in Putrajaya, Malaysia, about withdrawing from the Rome Statute that established the International Criminal Court, April 5, 2019.

Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad speaks to reporters in Putrajaya, Malaysia, about withdrawing from the Rome Statute that established the International Criminal Court, April 5, 2019.

Malaysia’s Pakatan Harapan government has fallen short of fulfilling campaign promises to improve the country’s human rights standing a year after coming to power in a historic election, two leading global rights watchdogs said Wednesday.

Human Rights Watch (HRW) and Amnesty International held a joint news conference to assess the rights record under Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad’s government, on the eve of the first anniversary of polls that saw the UMNO party swept out of power for the first time in 61 years.

“Human rights in the international system, the duty bearers are the government. It means the government has the responsibility to protect the human rights of all,” said Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director for Human Rights Watch. “So when we don’t see that happening, when we see the step back from these pledges, it raises real concerns on political commitment.”

A year was enough time to undo actions by the previous government, said Shamini Darshni Kaliemuthu, the head of Amnesty’s Malaysia office, during the press conference near Kuala Lumpur.

“PH [Pakatan Harapan] planned a lot of things in its manifesto. It takes political will,” she told reporters. “There are decisions that can be made by the cabinet, whether to abolish, amend or review. Political will is lacking now.”

Meanwhile, Prime Minister Mahathir, who spoke to reporters on Monday to mark the anniversary, gave his cabinet a “five out of 10” score and said its members were learning how government functions.

“And we have one single objective, to bring back the Malaysia that we knew before,” said Mahathir, who had previously served as prime minister, from 1981 to 2003, when he led the United Malays National Organization (UMNO) and its Barisan Nasional coalition.

Government officials could not be immediately reached on Wednesday to respond to the comments from HRW and Amnesty.

Mahathir returned to power after leading the opposition Pakatan coalition, whose electoral platform included human rights reform, to a stunning victory on May 9, 2018.

“I am very conservative. I have been in the government for 22 years and I know how government functions, but these people (ministers) are new, they do not know how a government functions,” Mahathir said on Monday. “They are so afraid of being accused of wrongdoing and all this makes their decision-making more difficult.

“But they are learning very fast. Sometimes they come to me because I have the experience. I have to teach and guide them so that they can perform,” he added.

![190508-MY-HumanRight-inside620.jpg Shamini Darshni Kaliemuthu (left), executive director of Amnesty International Malaysia, appears with Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director for Human Rights Watch, at a press conference in Petaling Jaya, Malaysia, May 8, 2019. [Radzi Razak/BenarNews]](/english/news/malaysian/Pakatan-human-rights-05082019152257.html/190508-MY-HumanRight-620.jpg/@@images/90f66b4e-781d-4bb9-80aa-703874ed9a08.jpeg)

‘Follow through’

The Pakatan government had not gone far enough in rights-related efforts during its first year in power because officials had not been able to move past public opinion and rise above “destructive” politics, Robertson said.

This was disconcerting and entirely out of proportion, he said, because the Pakatan alliance had promised reforms and commitment to human rights.

“The government should recognize that further delays in ending abusive systems and laws will only mean further harm for the Malaysian people,” Robertson told reporters in Petaling Jaya.

“They need to understand that they are elected and have made commitments, and follow through on them, things will be all right.”

Robertson pointed to Mahathir backpedaling in November 2018 on a campaign promise to sign the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD). The government had faced a backlash from critics who said it could undermine privileges enshrined in the constitution for the ethnic Malay majority.

Robertson said Malaysia was not unique because many countries had people of different races and religions living side by side, and were able to ratify U.N. conventions, implement human rights law and ensure that peace and tranquility was maintained.

However, in its annual report which was published in January and covered the previous year, Human Rights Watch described the atmosphere for free speech in Malaysia as dramatically improved since Pakatan took over last May. In April, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) said the climate for a free press in the country had also improved considerably under the new government.

In a brief statement to the media, Mahathir’s office had confirmed that the government would abandon the U.N. convention and continue to uphold the constitution, but did not provide a reason for that decision.

Five months later, Mahathir withdrew from the Rome Statute, which forms the basis of the International Criminal Court (ICC).

He told a news conference last month that the country would not accede to the Rome Statute because opposition politicians had been able “to create confusion in the minds of the people, that this law negates the rights of the Malays and the rights of the rulers.”

“This is not because we are against it, but because of the political confusion about what it entails, caused by people with vested interests,” Mahathir said.

Last December, the new government appeared to abandon electoral pledges to repeal provisions of controversial national security laws.

A special committee appointed by the government had concluded that such legislation – which drew criticism for potential human rights abuses – was needed to protect Malaysia from organized crime and terror threats, Home Minister Muhyiddin Yassin said at the time.

These national security laws included the Security Offenses (Special Measures) Act, or SOSMA, a law that was introduced six years ago to fight terror threats, and the Prevention of Terrorism Act (POTA).