Deep South artists portray Thai-Malay struggle in life and culture

2022.07.04

Bangkok

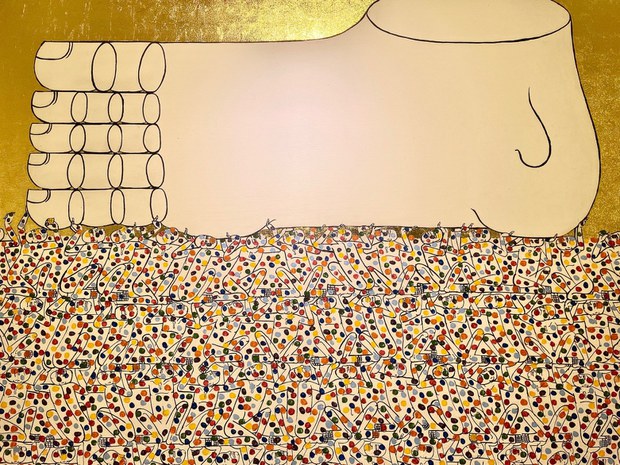

“Under 2021” by Thai artist Korakot Sangno was part of an exhibition by seven Deep South artists at VS Gallery in Bangkok, June 15, 2022.

“Under 2021” by Thai artist Korakot Sangno was part of an exhibition by seven Deep South artists at VS Gallery in Bangkok, June 15, 2022.

Contemporary art from Thailand’s violence-wracked Deep South can open conversations and battle stereotypes about the impoverished region, practitioners say.

That was a motivation for a recent show at a Bangkok gallery featuring seven artists from the southern border region: to help people in the nation’s capital see how life is different in the mainly Muslim and Malay-speaking border region, which is home to an ongoing insurgency.

“The idea is to showcase the works of the marginalized and increase the understanding of issues affecting residents of the restive Deep South,” said Thai art collector Voravuj Sujjaporamest, owner of the VS Gallery.

“Bangkok people harbor a negative bias against southern Thailand, even though most have not visited the place or met the people.”

Jehabdulloh Jehsorhoh, one of the artists showing his work, was an art student at Prince of Songkla University in January 2004 when the insurgency reignited as separatist outfit Barisan Revolusi Nasional launched an attack on security installations and seized weapons.

Three months later, the military killed more than 30 militants holed up inside a historic mosque in Pattani, while in October that year, a demonstration in neighboring Narathiwat turned violent and dozens of detained protesters died of suffocation while being transported to a military camp.

Since then, more than 7,300 people have been killed and 13,500 injured, according to Deep South Watch, a local think-tank.

In 2012, spurred by those events, Jehabdulloh created Patani Artspace, a 10-member gallery in the Deep South.

“I founded it because of the 2004 incidents. I saw the need to create a space for conversations between local people and visitors using contemporary art,” he said, adding that most people think art in the Deep South is purely functional, such as batik cloth or Kolae traditional boat painting.

Today, Jehabdulloh is an associate professor at his alma mater and regularly travels across the country to explain what it’s like to be from the Deep South to help people better understand the region.

In August, Patani Artspace is organizing the region’s first contemporary art exhibition in several cities where more than 50 Southeast Asia artists will showcase their work.

The Deep South encompasses Pattani, Narathiwat and Yala provinces along with four districts of Songkhla province.

Pattani and Narathiwat are the poorest provinces in the country, with poverty rates of 34.2 percent and 34.17 percent, respectively, according to a 2019 World Bank report, compared to the nationwide rate of 6 percent.

“Most Thais never dare visit these areas, not only because of the distance but because of the rumors about the incidents of violence, as well as the cultural and religious difference from the rest of the country,” Voravuj told BenarNews.

“These reasons make them politically and culturally marginalized. Meanwhile, the Deep South people have had to learn to heal themselves with a strong sense of cultural identity to fight alienation.”

Jehabdulloh said Deep South artists face two main challenges. The first is economic, as “the power in the arts industry is centralized in Bangkok.”

The second relates to content, as much of the Deep South art “does not please the government because we present the truth, especially human rights issues, injustice stories that happened in the areas, and the violence.”

He said security forces have frequently visited Artspace and though they never stopped an exhibition, exchanges have been mostly negative.

“We were not threatened, but the authorities would apply psychological tactics with us … asking why we are working on certain issues – why don’t we draw beautiful flowers?” Jehabdulloh said.

Below is a selection of Deep South art displayed at the VS Gallery in June:

Jehabdulloh’s seven life-size shooting targets made of rusted zinc plate on wood with a silhouette of a man standing with boots, tanks and weapons next to his head showcase the injustice and oppression due to pervasive power in a security state.

Galvanized sheets, commonly used to build homes and sheds, represent grassroots people and their values. The artwork’s messages were inspired by the Bahasa Melayu Patani language.

‘Unreal Peace’

Artist Pichet Piaklin stuck .45-caliber and 9mm brass shells on wooden flagpoles to showcase that peace “can exist only because there are wars.”

“Peace in human imagination is only a dream, like a mere temporary truce. Conversely, wars exist incessantly in every corner of the world,” he said.

‘Suffering in Patani’

Muhammadsuriyee Mosu created a series of patterned prints of Java doves with a red string clipped to parts of their bodies “to reflect the feeling of citizens in the areas under emergency acts and martial law.”

“The special laws never make the situation better or more peaceful for the people but allow many to be arrested and tortured to confess,” Mosu said.

‘Under 2021’

Korakot Sangnoy used Chinese ink, acrylic and gold leaf on a giant canvas to create an image of hundreds of kneeling people carrying a giant foot. The artist said it portrays oppression caused by people in power manipulating, monitoring and getting rid of anyone who stands up and asks questions.

“Many people have surrendered to the power that dominates their thoughts and beliefs,” he said. “This thing exists by strict enforcement of rules and corrupt trickery to control their lives and minds.”

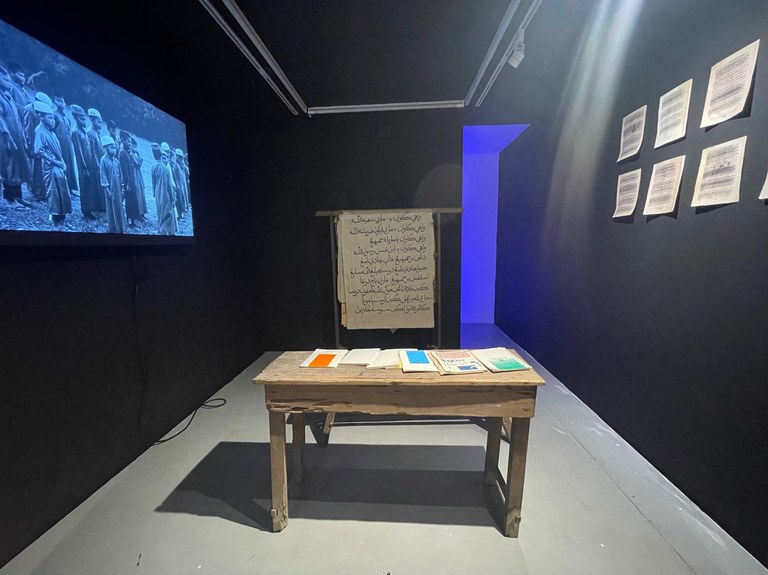

‘Tadika’

As a child, Wanmuhaimin E-taela attended Tadika, a religious primary school that receives no government support. His exhibit featured torn textbooks, a blackboard, a dilapidated desk and a bench to showcase the role of Thai nationalism in creating a single national identity at the expense of other ethnic-religious-cultural ones including Malay-speaking Muslims from the Deep South.

‘Melayu … Unpopular’

Muhammadtoha Hajiyugot’s print shows Michelangelo’s David and Venus de Milo wearing sarong and batik fabrics to portray the impact of technology changing society, especially the influence of social media and pop culture dominating the world.

With freehand sketching and the use of geometric lines that penetrate the statues, Muhammadtoha said he is asking the Thai-Malay people about the impact of pop culture in daily lives, faith, and society.

‘Sandals’

Esuwan Chali engraves shapes of reptiles, a symbol of bad luck in Thailand, on the insoles of everyday wear in a video installation behind rubber sandals that visitors are asked to wear. The artist said it shows the trauma of oppressed and exploited people being trampled by the authorities.

Nontarat Phaicharoen and Pimuk Rakkanam in Bangkok contributed to this report. All photos by BenarNews.