With Duterte in ICC custody, Southeast Asians see hope for region’s victims

2025.03.14

Washington

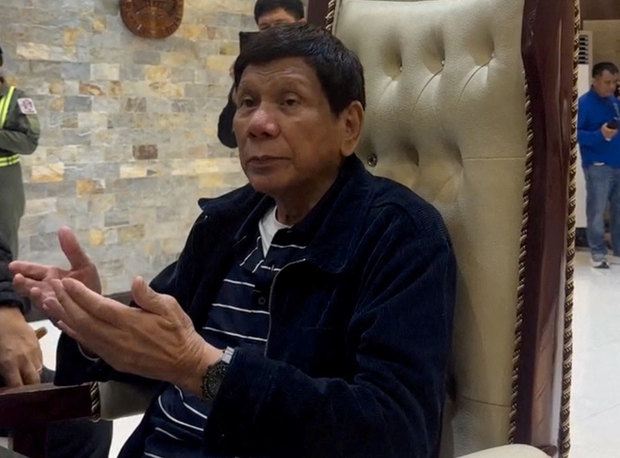

Former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte is seen at a location said to be the Villamor Air Base in Metro Manila, after he was arrested on a warrant by the International Criminal Court, in this image taken from a social media video, March 11, 2025.

Former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte is seen at a location said to be the Villamor Air Base in Metro Manila, after he was arrested on a warrant by the International Criminal Court, in this image taken from a social media video, March 11, 2025.

The arrest this week of a former Philippine president on an International Criminal Court warrant would have “made Hun Sen unable to sleep,” an exiled critic of the ex-Cambodian prime minister said.

Kim Sok, the critic, struck an optimistic tone about justice being served to past and present Southeast Asian leaders accused of serious human rights violations like the Philippines’ Rodrigo Duterte and Cambodia’s Hun Sen.

But some observers maintained a bleak outlook for the region’s victims of political or racial persecution.

Duterte’s arrest on Tuesday to face trial on charges of crimes against humanity committed during his war on illegal drugs demonstrates the ICC’s potential to hold leaders accountable, said Eddy Pratomo, an Indonesian expert in international law.

“The current Philippine government, under President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. cooperated with Interpol, making [Duterte’s] arrest possible,” Eddy, an ICC expert and professor at Diponegoro University in Semarang, told BenarNews.

“This is a rare scenario, as many countries, especially those with active leaders accused of crimes, refuse to cooperate with the ICC. … For sovereign states with robust legal systems, the ICC’s reach is limited,” he added.

Eddy was referring to what many see as an ICC arrest tied to Philippine politics.

In 2022, Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. contested the national election with Duterte’s daughter Sara, but has since fallen out bitterly with her and her family.

And the Marcos government helped Interpol carry out the ICC's warrant by sending police to arrest Duterte.

Marcos Jr. is the son of the late Philippine strongman Ferdinand E. Marcos, who declared martial law in the country in 1972. During the late ex-president’s tenure, 70,000 people were imprisoned, 34,000 tortured and more than 3,200 killed, according to Amnesty International.

RELATED STORIES

Philippine drug-war survivors: Duterte’s ICC arrest marks first step toward justice

Argentina court calls for arrest warrant for Myanmar junta chief

International criminal court seeks arrest warrant for Myanmar junta chief

In Cambodia though, the exiled critic Kim Sok said, a potential future prime minister from Hun Sen’s own party wouldn’t shield him if the ICC issued an arrest warrant for the former Cambodian strongman. Hun Sen’s son, Hun Manet, is currently prime minister.

“[E]ven if a successor comes from his ruling Cambodians People’s Party, they would likely pave the way for his arrest, because if they don’t cooperate, they would be complicit in committing crimes with Hun Sen,” Kim Sok told Radio Free Asia (RFA), a news service affiliated with BenarNews.

“This development [would have] made Hun Sen unable to sleep permanently,” added Kim Sok, who went into exile in 2018, fearing for his safety if he stayed in Cambodia.

New York-based Human Rights Watch noted in 2015 that Hun Sen had been linked to “extrajudicial killings, torture, arbitrary arrests, summary trials, censorship, bans on assembly and association, and a national network of spies and informers intended to frighten and intimidate the public into submission.”

Just as the Marcoses, Dutertes and Hun Sen have spawned political dynasties, neighboring Indonesia last year also elected a president and a vice president linked to political clans.

But it is the election of Prabowo Subianto as Indonesian president, which followed the 2022 victory of Marcos Jr. and Sara Duterte that led BenarNews columnist Zachary Abuza to declare a form of “historical amnesia” in Southeast Asia.

Prabowo has a direct familial link to Suharto. He used to be married to a daughter of the late dictator, who ruled the country with an iron hand for 32 years.

Suharto rose to power after a bloody anti-communist purge in the 1960s. It is widely assumed he sanctioned the killings of an estimated 500,000 to 1 million people, and in 1998 ordered the violent suppression of student protests.

And Prabowo, a former army general has been accused of links to or orchestration of several human rights violations during his military career. However, no charges have ever been filed against him nor has he been tried in court.

Bedjo Untung, a survivor of the anti-communist purges, spent nine years in military detention under Suharto’s regime, enduring forced labor and torture.

“I feel encouraged by the news of Duterte’s arrest. A former president is being held accountable for crimes against humanity and war crimes,” Bedjo, who is chair of the 1965 Victims’ Advocacy Foundation, told BenarNews.

“This gives me hope that justice can also be served in Indonesia, where impunity has prevailed for nearly 60 years. We have been ignored for decades.”

In November, ICC Prosecutor Karim A.A. Khan decided to request an arrest warrant for Myanmar military chief Sr. Gen. Min Aung Hlaing over his association with alleged crimes against humanity against the Rohingya minority, from August to December 2017.

The Myanmar military and police in 2017 killed tens of thousands of the persecuted Muslim Rohingya in response to an attack by insurgents from the group on police and army posts in Rakhine state.

Min Aung Hlaing is still military chief and currently runs Myanmar. He toppled an elected government in February 2021.

Tun Khin, the founder of the Burmese Rohingya Organization UK, who filed a lawsuit against Myanmar’s military leaders in an Argentine court, said he was pleased to hear about Duterte.

“Anyone can commit crimes, but no one can escape justice. Eventually, you will be arrested,” he told RFA Burmese.

“Even though [Min Aung Hlaing] currently holds power illegally, there will come a time, whether when he is no longer in power or if he travels abroad, that he will be arrested. The arrest of Duterte serves as a clear warning to Myanmar’s military leaders.”

Meanwhile, Southeast Asian governments have largely remained silent on Duterte’s arrest.

When BenarNews asked for a reaction, Indonesian Foreign Ministry spokesperson Rolliansyah Soemirat said, “we have no comment on this matter.”

Thai government spokesperson Jirayu Huangsap said that Bangkok would not weigh in.

“This is a matter of international politics. It doesn’t concern Thailand, so we cannot comment on it,” he told BenarNews.

‘ASEAN culture’

Thai analyst Thanaporn Sriyakul said leaders of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) were silent “because they don’t want to be caught in the crossfire.”

In Thailand, those in power, whether from an elected government or the military, “firmly maintain” the culture of impunity, said Thanaporn, chairman of the Political Science Association at Kasetsart University.

“That’s why we don’t see any action taken in cases such as the Tak Bai massacre in 2004 or the Oct. 6, 1976, massacre … No high-level leader has ever been held accountable for these matters.”

“Therefore, it’s impossible for high-level leaders in Thailand to be prosecuted like Duterte.”

On Oct. 25, 2004, during the Islamic holy month of Ramadan, 85 unarmed protesters in Tak Bai, in Muslim-majority Narathiwat province, were killed during a protest in front of a police station.

And in October 1976, more than 40 people were killed and over 150 injured when police stormed Thammasat University’s campus in Bangkok to break up a demonstration by thousands of students protesting the return of a former military ruler, Thanom Kittikachorn.

“Those in power in ASEAN countries share mutual benefits and connecting advantages in one way or another,” said Kasetsart University’s Thanaporn.

“The culture of impunity is already an ASEAN culture.”

Tria Dianti in Jakarta and Jon Preechawong in Bangkok contributed to this report along with RFA Khmer and Ye Kaung Myint Maung from RFA Burmese.